Gratitude and Guilt: Mixed Feelings on Thanksgiving

What once was my favorite holiday has turned into a decolonization effort

“In 1621, colonists invited Massasoit, the chief of the Wampanoags, to a feast after a recent land deal. Massasoit came with ninety of his men. That meal is why we still eat a meal together in November. Celebrate it as a nation. But that one wasn’t a thanksgiving meal. It was a land-deal meal. Two years later there was another, similar meal meant to symbolize eternal friendship. Two hundred Indians dropped dead that night from an unknown poison.”

- Tommy Orange, There There

As I grew up, I became obsessed with picking my number one favorite things. Once I said something was my favorite, it was basically sealed for life, stamped for eternity as “Lillian’s Favorite.” Many of those things remain the same to this day as an adult. Purple is my favorite color. Sushi is my favorite food. “I Feel For You” by Chaka Khan is my favorite song. So when it came to holidays, it was tough because there were so many good ones. There’s dressing up and collecting candy at Halloween, wearing pretty dresses and going to Church on Easter, exchanging gifts and waiting for Santa during Christmas; how could I pick one favorite?

Eventually, somewhere around middle school, I announced that Thanksgiving was my favorite holiday. It was the one time of year that I got to see a lot of extended family, the food was delicious (I’m a big foodie), and the last Thursday of November signified the beginning of Christmas in my house. Not to mention we’d always host, so we’d eat in our dining room and set the table with all the fancy plates, candles, the table runner, and crystal glasses. I grew to love Thanksgiving, and relished being “different” for picking it as my favorite holiday, because virtually no one else I knew picked it as their favorite. I once got in a small fight with a girl in high school who claimed that Thanksgiving was “Christmas’s forgotten cousin” and that no one actually liked celebrating it. I argued that it was my favorite holiday and that I looked forward to it every year. It was not the forgotten cousin in my book.

But once I hit college, I started to take my literature classes and was required as an English major to take a Race, Ethnicity and Sexuality course; essentially, a course where all the authors that we read were the same race, ethnicity, and/or sexuality. I picked Native Literature, taught by a professor from North Dakota’s Turtle Mountain Chippewa Reservation. The first book we read was Tommy Orange’s There There.

“We are Urban Indians and Indigenous Indians, Rez Indians, and Indians from Mexico and Central and South America. We are Alaskan Native Indians, Native Hawaiians, and European expatriate Indians, Indians from eight different tribes with quarter-blood quantum requirements and so not federally recognized Indian kinds of Indians. We are enrolled members of tribes and disenrolled members, ineligible members and tribal council members. We are full-blood, half-breed, quadroon, eighths, sixteenths, thirty-seconds. Undoable math. Insignificant remainders.”

- Tommy Orange, There There

Of course, I understood the pilgrim story was saccharine, of course, I learned about the Trail of Tears in history class, of course, I knew Disney’s Pocahontas was fabricated. But it wasn’t until this class, and the personal stories shared by my professor of his experiences as a Native person, did I really start to open my eyes and recognize my ignorance. I started doing deep dives into traditional dances and throat-singing, educating myself and honoring the missing and m*rdered young Native women, learning the meaning of tattoos for other indigenous peoples around the world (i.e. Māori face tattoos), and looked up Native artists and small businesses. Later that spring, I visited the Field Museum in Chicago to look at their exhibition titled, “Native Truths: Our Voices, Our Stories.” I wanted to learn as much as I could.

Only once I took this class did I realize how prevalent the idea of Native people as “mascots” were. I remember my professor talking about football teams like the Chiefs with their arrowhead logo, or how hockey fans show up to Chicago Blackhawks games wearing fake headdresses and regalia. He couldn’t understand how something like Native identity could be worn as a costume or used as a gimmick. Sitting in his class, I couldn’t either. It was amazing to me how Native imagery appeared everywhere for things like branding, logos, or aesthetics.

“We have all the logos and mascots. The copy of a copy of the image of an Indian in a textbook. All the way from the top of Canada, the top of Alaska, down to the bottom of South America, Indians were removed, then reduced to a feathered image. Our heads are on flags, jerseys, and coins. Our heads were on the penny first, of course, the Indian cent, and then on the buffalo nickel, both before we could even vote as a people—which, like the truth of what happened in history all over the world, and like all that spilled blood from slaughter, are now out of circulation.”

- Tommy Orange, There There

Even before this class, I had started to learn the reality of how Native people were treated on the first Thanksgiving, and I felt the guilt gnawing away at my stomach. I didn’t feel right about Thanksgiving being my favorite holiday anymore. I still loved the family aspect and I enjoyed the food, but as I got older, the holiday began to change. I watched it morph into something I felt terrible about celebrating, and as moved away to college and my family started hosting it less and less each year, it didn’t give me the same warm, fuzzy feelings it used to.

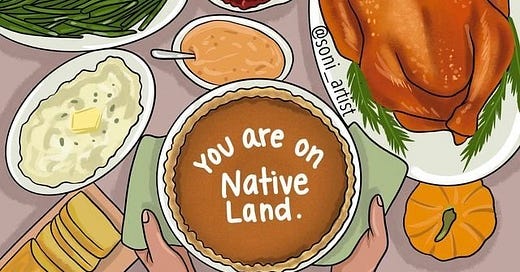

Needless to say, Thanksgiving is no longer my favorite holiday. In fact, I don’t have one particular favorite holiday, period. I’m pretty sure I gave up that practice of picking favorites a long time ago. I can’t turn back to how I felt before now that I know the truth. Post this class and moving back home, I’ve tried to balance both feelings. I can recognize the falsity that is the Thanksgiving narrative while also enjoying a good meal with my family. I can still take the day to tell those I love that I’m thankful for them. I can make posts on social media about Native history while also having a slice of pumpkin pie. At least, I think I can. It’s a hard balancing act. I’ll see how this Thursday goes.

“The wound that was made when white people came and took all that they took has never healed. An unattended wound gets infected. Becomes a new kind of wound like the history of what actually happened became a new kind history. All these stories that we haven’t been telling all this time, that we haven’t been listening to, are just part of what we need to heal.”

- Tommy Orange, There There

- Lillian

(P.S. The cover photo for this piece is from Soni López-Chávez. You can find her on Instagram and Facebook. Check out her artwork!)